I’m not usually the biggest fan of long-format podcasts. It’s not that I don’t enjoy them, it’s more a matter of time. Sitting through a two-hour conversation without distraction is a rare luxury.

That said, when I saw Simon Sinek had returned as a guest on Steven Bartlett’s podcast The Diary of a CEO, I tuned in immediately.

There are two main reasons I consider listening to Sinek a valuable investment of time. First, he makes me think. I don’t always agree with him, but I appreciate thinkers who challenge my perspective – especially when they articulate ideas I either hadn’t considered or disagreed with prematurely. Second, he has an exceptional ability to communicate complex thoughts with clarity and structure. Time and again, I find myself thinking: “That’s exactly what I’ve observed, it is just better articulated than I ever managed.”

This episode, like many others on the podcast, was engaging and thought-provoking. But one idea in particular stuck with me. Sinek shared (and I’m paraphrasing here) the following hypothesis:

Breakthrough innovation happens in small companies.

Large corporations rarely innovate themselves. Instead, they acquire startups. The reason? Big companies have lost their ability to dream ambitiously. Their goals are almost always within the realm of what’s possible using their existing resources. Startups, by contrast, dream far beyond what they can afford or practically achieve. They’re forced to be creative out of necessity. often working outside their resource constraints, hacking their way forward. That scarcity breeds innovation.

This really hit home for me. Having worked in R&D departments of large corporations, I’ve personally felt the frustration of pitching truly novel ideas, only to have them shot down. And this is not because they weren’t viable or promising, but because they didn’t align with short-term resource allocations, or because of the all-too-common fear of self-cannibalization.

It is reassuring to understand that this issue is not confined to my previous employers; it is a systemic problem. One striking statistic underscores this reality: over 65% of new drug approvals by major pharmaceutical companies originate from acquisitions, not in-house R&D.¹ That’s not an anomaly. In tech, the pattern is similar: Google’s biggest success stories are YouTube, Android, and DeepMind which were all acquired at some point in time. Facebook (now Meta) bought Instagram, WhatsApp, and Oculus to secure its position.

So what’s going on here? Why do large corporations that are often flush with cash, talent, and data, lose their edge when it comes to true innovation?

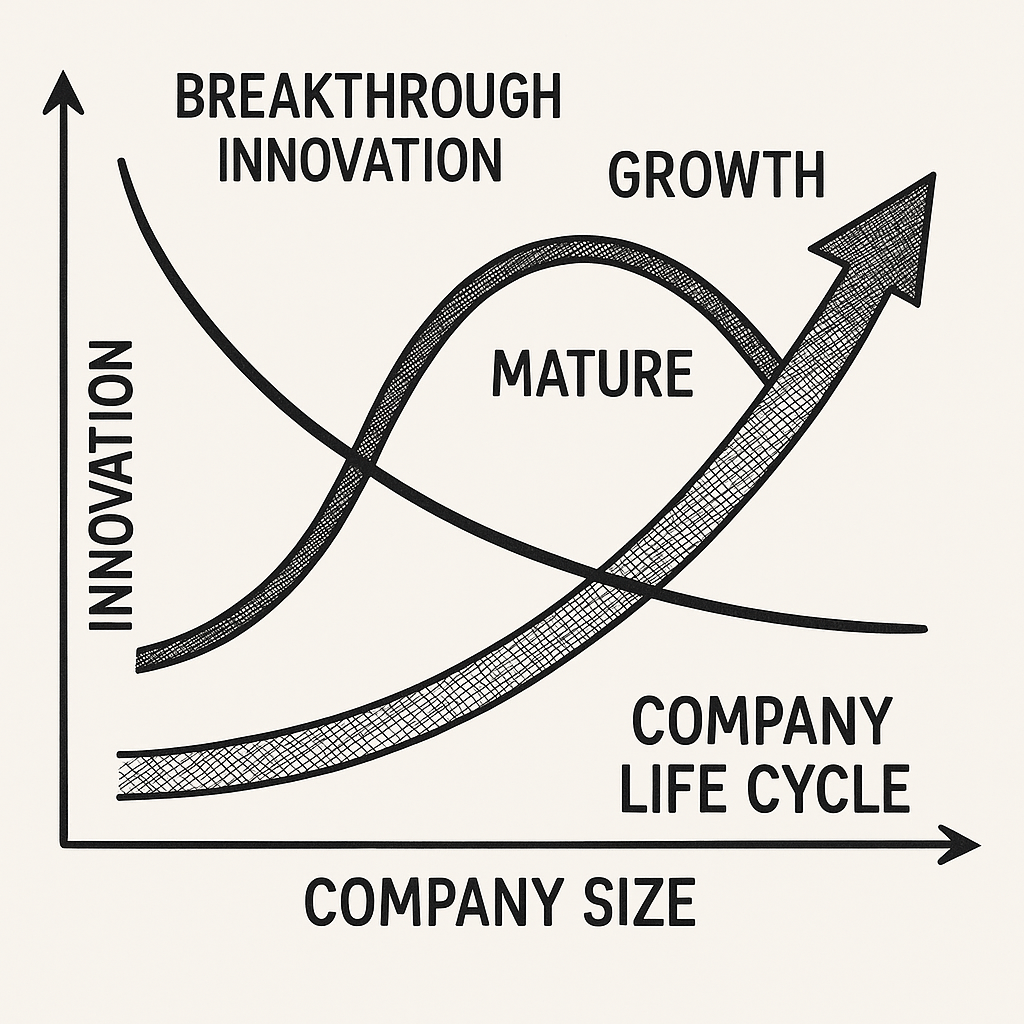

One way to understand this is through the lens of the corporate life cycle, a framework popularized by finance professor Aswath Damodaran. Like living organisms, companies move through stages: startup, growth, mature, and decline. Early-stage companies take bold risks because they have to. Growth is their only option. But as companies mature, they accumulate not just resources, but bureaucracy, aversion to risk, and pressure to protect what they’ve built.

By the time a company enters maturity, its focus often shifts from creating the future to defending the present. Managers are measured by quarterly earnings, not breakthrough ideas. Innovation gets deprioritized in favor of operational efficiency. This isn’t necessarily incompetence, it’s structural. A mature company’s systems are optimized for predictability, not surprise.

This also explains why acquisition becomes the default innovation strategy. It’s simply safer to buy proven growth than to incubate uncertain ideas internally. In Damodaran’s terms, companies in this stage often prefer to “harvest” rather than “invest.”

But here’s the tension: true innovation doesn’t emerge from harvest mode. It comes from dreaming beyond your means. That’s what startups do. They bet on the improbable and because of that, they sometimes discover the extraordinary.

So the real question isn’t just why large corporations struggle to innovate. It’s whether they can break out of their own life-cycle logic and if not, what new structures or cultures might allow the scale of a big company to coexist with the audacity of a small one.

In that light, consider Meta’s latest push into superintelligence. The company has committed billions to building frontier AI models, aiming to compete with (or surpass) OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Anthropic by attracting the most talented with absurd salaries. But is this true innovation or just the corporate equivalent of throwing money at the problem?

If Sinek’s hypothesis holds – that innovation is born out of constraint – then Meta’s approach raises important questions. Can a company operating at that scale, with virtually unlimited resources, still dream like a startup? Or is it simply trying to buy the conditions that once made it creative?

Because if big leaps really do require small-company desperation, then pouring capital into AI might produce progress, but it won’t be the kind of transformative, risk-bending breakthroughs that change the game. So, I am curious how this is playing out.

To me, it seems like innovation is not just a function of how much you invest. It’s where you’re standing when you dream.

Leave a comment